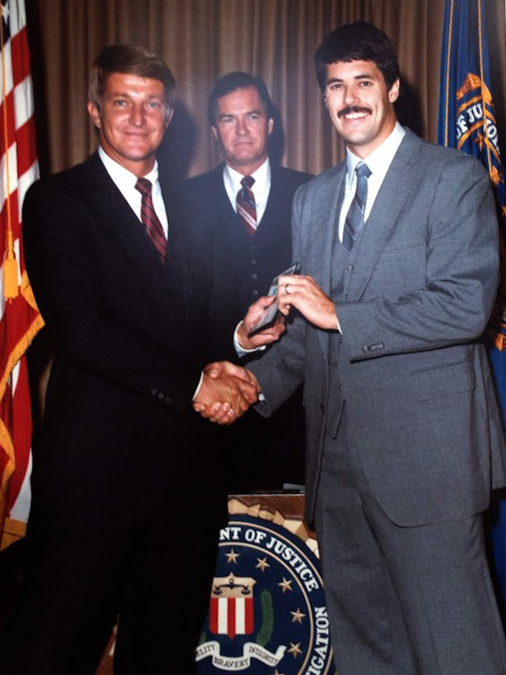

In October 1983, Harry Trombitas receives his Federal Bureau of Investigation credentials during a graduation ceremony, marking the beginning of his service with the FBI.

It sounds like a scene from “Men in Black:” strange men in suits offering a chance to join them and protect the nation from threats. Harry Trombitas said yes — minus the memory wipe.

The decision would take Trombitas, a 1982 graduate of Creighton University, from Creighton University’s Department of Public Safety to a nearly three-decade career with the FBI, where he worked in some of its most violent cases. Long before the badge and the suits, Trombitas credits both Creighton’s campus and its emphasis on service, faith and people that set him on that path.

“Creighton was just a wonderful environment,” Trombitas said. “It had a great reputation, incredible faculty and staff, and it focused on the whole person — not just academics.”

While attending Creighton, Trombitas worked as a supervisor in what would become the university’s Department of Public Safety. At the time, campus security relied on an external guard system that left many dissatisfied. Trombitas and his colleagues were tasked with building something new and personal.

“We started the public safety department from the ground up,” he said. “We hired officers, trained them, bought vehicles and met with faculty and staff, so they knew we weren’t an outside company. We were their people.”

The department emphasized prevention and student support, offering escort services, vehicle assistance, self‑defense education, and crime‑prevention initiatives. One such effort included “gotcha cards,” light‑hearted reminders placed on unattended valuables to encourage awareness.

“The goal was to keep students safe, not to intimidate them,” Trombitas said. “That kind of approach really mattered on a college campus.”

Trombitas remembers Creighton not just as a workplace or academic institution, but as a tight‑knit community, something reflected even in everyday friendships. One of his favorite memories involves helping a close friend at Creighton’s dental school.

The friend, Bill, eager to complete a required cavity‑filling prerequisite, discovered Trombitas had a small cavity and volunteered to fix it. But after administering Novocain, Trombitas quickly realized something was wrong.

“He numbed the wrong side of my mouth,” Trombitas recalled, laughing. “I said, ‘I think the cavity’s over here.’ And [Bill] goes, ‘Oh, shit … It’s just a small one.’ [Bill] said, ‘If you can tolerate the pain, you know, please do because otherwise I got to go report up to the desk and that’s not going to look good for me.’”

Trombitas endured the procedure without anesthesia simply to help his friend succeed.

“Stuff happens, right? That’s what friends are for,” he said. “Those are the memories that stick with you.”

Despite his growing role in campus safety, Trombitas had never seriously considered a career with the FBI. That changed when agents began visiting Creighton.

“I kept seeing these guys show up at our [public safety] office … dressed in suits and found out they were FBI agents trying to recruit students on campus, especially the law school.”

Those encounters planted the seed.

“I struck up conversations with them and realized my background actually fit,” he said. “Once they learned I had a master’s degree, it really helped.”

His time in Omaha proved formative. Trombitas’ first FBI assignment exposed him to Nebraska’s most notorious crime of the century: the abduction and murder of three young boys by serial killer John J. Joubert. Assigned to support the victim’s family, Trombitas spent long days with grieving parents while also assisting the investigation.

“It was every parent’s worst nightmare,” he said, “but it taught me compassion and perspective. You see what crime really does to families.”

The experience also revealed the importance of collaboration.

“I saw how federal agents, local law enforcement and the media all worked together,” Trombitas said. “That teamwork stuck with me for the rest of my career.”

Over nearly three decades, Trombitas served in FBI offices across the country, including Omaha, St. Louis, New York City and Columbus. His work ranged from violent crime and bank robberies to organized crime, kidnappings, crimes against children and counterterrorism.

Trombitas found that it was difficult to identify which crime tips from the public belonged to because of the significant number of robberies.

“I started naming the bank robbers based on information that we gathered during our interviews at the bank after the robbery,” Trombitas said. “One teller told me, ‘Oh my god, this woman had the worst breath I’d ever smelled in my life,’ so she became the Bad Breath Bandit.”

Other nicknames followed, including the “Grandpa Bandit,” an elderly man who robbed a bank using a walker and was arrested before he reached the door.

In St. Louis, Trombitas worked undercover on a task force targeting auto‑theft rings and illegal chop shops. In New York City, he was assigned to an organized crime surveillance squad, tracking figures associated with the Mob like John Gotti.

Later, in Columbus, Trombitas handled some of the most serious cases of his career, including serial murder investigations. Throughout it all, he emphasized the importance of balance.

“You have to compartmentalize,” he said. “You still have to be a husband and a father. If you can’t separate the job from your personal life, it can really affect you.”

PHOTOS COURTESY OF HARRY TROMBITAS

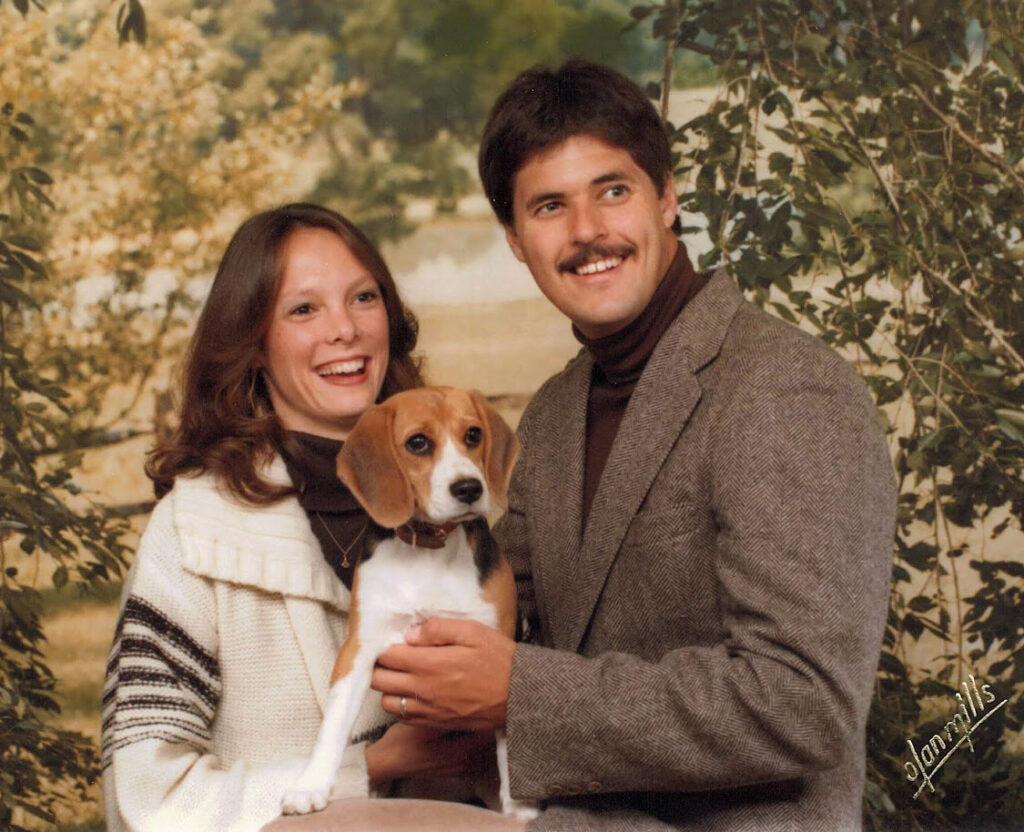

(Left Image) Harry Trombitas, his wife Barb, and their dog Daisy, around 1980. Trombitas was then working in Creighton University’s Public Safety Department.

(Right Image) Harry Trombitas in 1982 during his work on the Ferdinand Marcos case in Hawaii.

Despite frequent exposure to violence, Trombitas rejects the idea that his work made him cynical.

“There are far more good people in the world than bad ones,” he said. “That’s what I saw throughout my career.”

That belief was reinforced not only through cases, but also through the unlikely experiences the job afforded him — from crossing paths with country music group The Judds to sitting beside baseball legend Stan “the Man” Musial at a World Series game.

After retiring from the FBI in 2012, Trombitas continued working in security leadership, serving as a system vice president for OhioHealth hospitals and later directing the Police Executive Leadership College of Ohio. He also lectured at The Ohio State University and now works as a consultant on security and threat assessment.

“I’d still be [in the FBI] today if they didn’t have that age restriction,” Trombitas said. “I had so much fun and worked so many interesting things.”

He has since authored four true‑crime books detailing notable cases from his career, aiming to educate readers while honoring victims and investigators alike.

“I never planned to write books,” he said, “but people kept telling me these stories mattered.”

Looking back, Trombitas believes Creighton played a central role in preparing him for a career he never anticipated.

“Follow your passion, but don’t shut doors,” he advised students. “Try new things. You might discover a path you never expected.”

He also emphasized perspective.

“Don’t panic if you don’t have it all figured out,” Trombitas said. “Go make things happen — don’t wait for life to come to you.”

For Trombitas, Creighton’s value extends far beyond a diploma.

“Don’t overlook your time here,” he said. “The friendships, the values, they stay with you for the rest of your life. Take what Creighton gives you and carry it out into the world.”